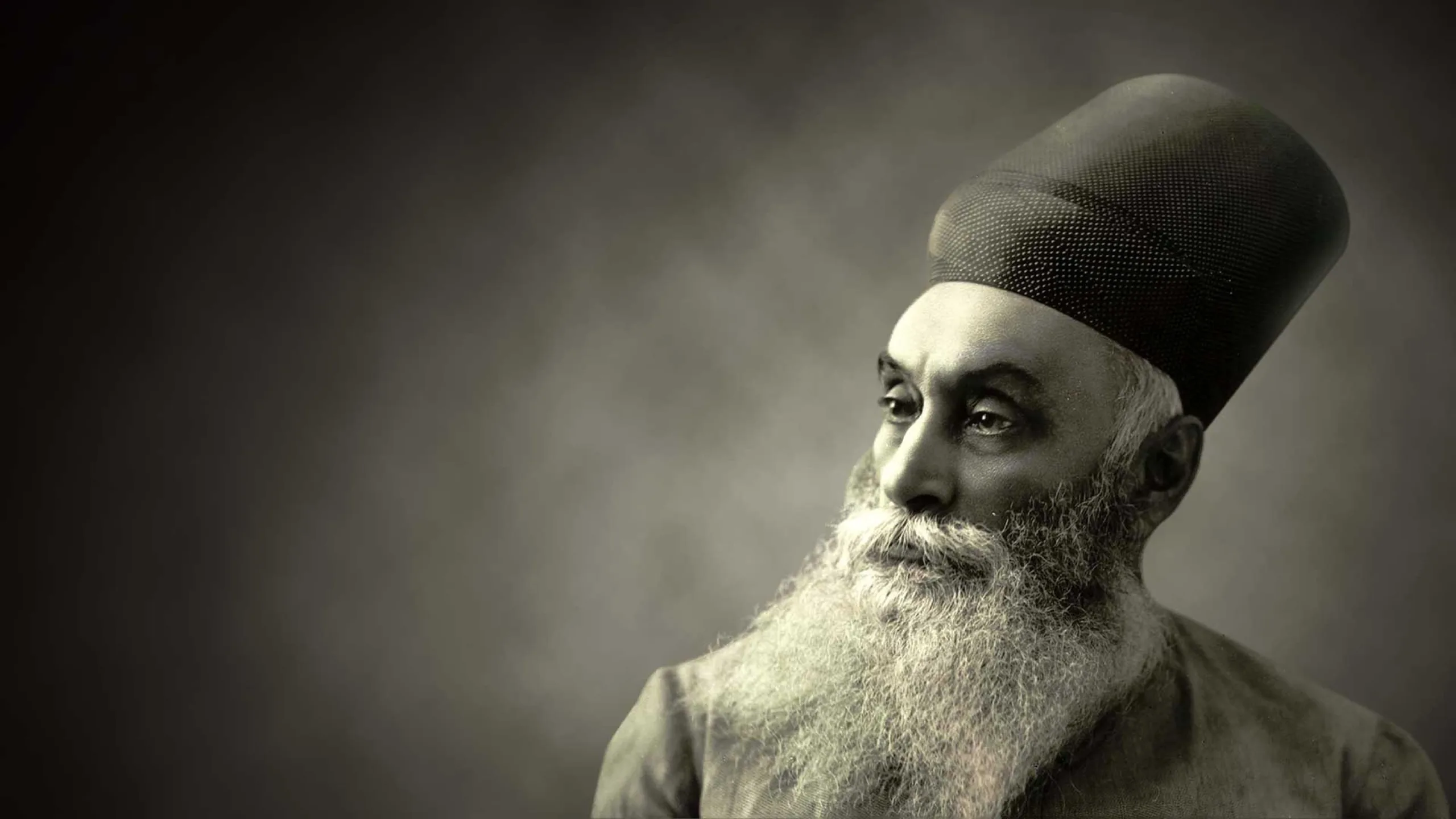

TataStories Jamsetji Tata

The following is an excerpt, published here with permission from Penguin Random House India and author Harish Bhat, from his book #Tata Stories, specifically the chapter “Never stop dreaming.”

TataStories Jamsetji Tata,The Tata Group’s founder, Jamsetji Tata, is renowned for starting extremely profitable, innovative businesses that subsequently shaped Indian industry. However, did you know that his life narrative also tells the account of a guy who never stopped dreaming?

Jamsetji had already built three extremely prosperous textile mills within the first thirty years of establishing the Tata Group in 1868: Empress Mills in Nagpur, Swadeshi Mills in Mumbai, and Advance Mills in Ahmedabad. In Jamshedpur, he had designed the first integrated steel mill in India, which would eventually become Tata Steel.In addition to planning the nation’s most ambitious hydroelectric power facility at Walwhan in the Western Ghats, he had started the process of building Mumbai’s magnificent Taj Mahal Hotel. He even built the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, the nation’s first full-fledged science research institution, and established the first Indian-only scholarships for higher education abroad.

When combined, these audacious and groundbreaking endeavors tell the tale of a full and satisfying life. Their preparation and implementation undoubtedly kept Jamsetji Tata very busy. In fact, “Had he no other title to recognition, his conduct of the mills would suffice,” observed one of his early biographers. Despite everything, he continued to see a plethora of other scenarios for his cherished country.

A really creative initiative he worked on was to build Mumbai with enough cold storage. By constructing a cold storage facility for fruits and fish, he hoped to boost the food supply and avoid ongoing shortages in the years after the terrible bubonic plague of the 1890s. thereabouts around 1900 or thereabouts, he started designing a massive structure that would be built on the site of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (formerly the Prince of Wales Museum).The construction of this circular edifice was intended to encircle a massive ice house, around which artificial ice production would provide structural cooling. The central ice house would provide adequate “air conditioning” for the offices and music halls situated around the building’s outside. These spaces would be available for rental. It was clear that Jamsetji was ahead of his time, as this project would never be completed during his lifetime. It would take twenty more years for his wish to come true, albeit in a different form, when refrigerators and sufficient cold storage were added to Mumbai’s famous Crawford Market.A further aspiration that Jamsetji fervently pursued was the creation of India’s own shipping company. According to him, a nation that depends on another country’s ships is always at a disadvantage. He also took issue with the British-owned Peninsular and Oriental (P&O) line, which at the time had a monopoly on shipping out of India, charging outrageous fees for the transportation of Indian cotton yarn. He thus went to Japan and, upon reaching a deal with the well-known Nippon Yusen Kaisha (NYK) line, he founded the Tata line. To that end, he purchased two ships, Annie Barrow and Lindisfarne, for the purpose of transporting Indian cotton goods and yarn alongside NYK’s Japanese ships at fair freight rates.

The Indian media applauded Jamsetji’s bravery for attempting to overthrow a powerful monopoly. But soon, the P&O line—which was financially supported by Indian taxpayers and revenues—decided to protect their monopoly and brutally destroy any competitors by lowering prices to astronomically unaffordable levels. In an uncommon move, they offered to shippers that signed appropriate declarations with them, free of charge, to bring Indian cotton to Japan. To no effect, Jamsetji Tata brought up this issue with the British government’s Secretary of State for India time and time again. Mumbai’s cotton mills eventually stopped providing contracts for the Tata line. As a result, the comparatively little Tata line was stopped down and the two ships were returned to England.

TataStories Jamsetji Tata, The project did, however, assist Japan’s NYK in gaining a first footing in the Indian market, which ultimately led to some rivalry and benefited Indian producers and retailers.

Despite this turnabout, Jamsetji continued to pursue other aspirational goals. He established a silk farm in Bangalore in order to apply many of the scientific sericulture concepts he had observed in Japan in India. As a result, he also developed the necessary skill sets in that nation. The Tata Silk Farm was a very prosperous business. The farm gave the local silk industry a boost in the past, but it is no longer in operation. Some of the initial students at the Tata Silk Farm were the titans of Indian sericulture, such Appadorai Mudaliar and Laxman Rao. In Bangalore, the Central Silk Board was also founded in 1949, a long time later.

Encouragement of Egyptian cotton cultivation in India was yet another goal. Here, Jamsetji Tata wanted to assist Indian mills in spinning yarn with finer counts, and Egyptian cotton was a prime candidate for this purpose. He did extensive research on this topic and expressed worry about the overabundance of produced cotton items coming from nations such as Germany, Austria, Belgium, and England into the Indian market. Thus, in a call to action, he pleaded with all Indians to prevent the complete devastation of India’s “young and only” industry. “If India were allowed to grow the long-stapled varieties for herself, she would derive immense benefit in three different directions—such an expansion would assist agriculture, conserve the nation’s currency, and improve the exchange,” he vehemently contended.

In India, attempts to cultivate Egyptian cotton started in earnest. These endeavors were unsuccessful in many areas, but they were successful in several sections in the central provinces. As he became more involved in his steel, hydropower, hotel, and science education endeavors, Jamsetji Tata—who was already nearing the end of his life—came to the conclusion that, in view of the project’s costs and benefits, it would not be prudent to pursue it further.

Jamsetji was still capable of dreaming right up until the very end. He spent his final days in Europe seeking advice from renowned physicians. Though he was still in good spirits, his heart had become feeble, and he was unable to sleep and had severe breathing problems. So, if there was a good day in San Remo, Italy, he would go to the market and buy fresh fruits, which he loved to eat. Because of their high nutritional value, he started to dream of growing dates and other Mediterranean fruits in India. He passed away a few days later, surrounded by his family’s affection.

Although the nature of his last dream remains unknown, it is certain to have been one that rekindled his intense passion for India, the country he fought for and supported all of his life.

Dreams are something you should never give up. The visions that guide and enhance our life are called dreams. Jamsetji Tata never gave up dreaming during his life, even after founding such innovative and prosperous companies and facing several obstacles and setbacks. Why ought we to?

by,HHM